Borders and Eugenics

Immigration controls and eugenicist thinking are two sides of the same coin

Imaginary Lines and Tangible Consequences

I used to say that freedom smells like duty free perfume and tobacco, which are the first fragrances to assault your senses when you cross the border at Cairo International Airport. The olfactory experience is complemented by an auditory one: the rhythmic clicking and pounding of exit stamps into passports.

Conscription - or the fear of it - is a rite of passage for any Egyptian male over 18 who has male siblings and lacks dual citizenship, as is the dreaded medical exam that decides whether you are fit to serve and which makes army medics experts on simulation and malingering. One of the best days of my life was the day I was declared unfit to serve on account of my eyesight - I wrote a fictionalized story of the medical exam eleven years ago in a now-defunct Egyptian English language literary journal named Rowayat.1

Egypt’s conscription is a legacy of the rule of Mehmed Ali (1805-1848), who is celebrated as the ‘founder of modern Egypt’ in school textbooks, and whose dynasty ruled the country until the 23 July Revolution of 1952.2 For those who have not yet served, they cannot leave the country without written permission from the military authorities. The first page of every adult male’s passport has a sentence stating your ‘military status’. Mine says ‘غير مطلوب للتجنيد’, loosely translated as ‘not required to present for conscription’. This line means I can leave Egypt without being asked about my military service at the border. Those who have served must still obtain permission to travel until they are in their forties, for there is always the non-negligble chance that, as reserves, they will be called up.

For this reason, Egypt felt to me like an open-air prison measuring one million square kilometers. Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.’ I’m no lawyer, but being prevented from leaving my country because of conscription requirements sounded like a violation of my human rights - it certainly felt like it. When I arrive in the UK, the border officer asks me why I want to enter the UK and what I am intending to do there, and they have the authority to deny me entry. That I should not be allowed to leave my own country and denied exit at the border is absurd.

Borders are the ultimate exercise in fiction literalized as truth. A major aspect of the human genetic lottery is which lines you happen to be born within. They are imaginary, not corresponding to any natural entity, protests of nationalist historians notwithstanding. They are arbitrary: the comedian Bill Hicks, when asked ‘Are you proud to be an American?’ replied ‘I don't know, I didn't have a lot to do with it. My parents fucked there, that's about all.’ They are also unequal: a British person can decide on the spur of the moment to book an EasyJet flight and visit my country, while no Egyptian can do the reverse without going through the prohibitively expensive and exclusionary bureaucratic nightmare of applying for a visa and gathering all the necessary documents to prove they are not a parasite, scrounger, or skiver seeking to take advantage of the glorious welfare state’s coveted Universal Credit.

While an Egyptian must apply for a visa about three months in advance of any anticipated travel date to the UK, a British national can obtain a visa to enter Egypt on arrival. In comparison to a British national, I cannot get on the Eurostar or book a flight to Cyprus just because I feel like it. I must either apply for a Schengen visa months in advance, or content myself with a staycation in Skegness. Though the UK and Ireland constitute a Common Travel Area, having Indefinite Leave to Remain does not authorize me to board a plane to Dublin on a whim - but if I go to Belfast I can cross the imaginary line that separates the Protestants from the Catholics and enter the Republic.

Medical Borders

You do not have to be trying to enter or exit a country to encounter the violence of the border. Borders are instantiated in myriad administrative guises, with pernicious human consequences. Working in the NHS, I am familiar with medical borders. The case of a refugee from a Middle Eastern country detained under the Mental Health Act by the police after performing a public suicidal gesture to protest his forced relocation to another city comes to mind. A native can engage in a suicidal gesture out of frustration at intolerable life circumstances, which allows them to gain admittance to a psychiatric hospital for respite, receive ‘three hots and a cot’,3 and draw on a reservoir of sympathy. A refugee with no legal status in the country who engages in the same suicidal gesture does not have the same cultural and social capital to draw on.

The person I have in mind did not even have the freedom to sleep rough and be homeless. Admittance to hospital may delay the relocation pending an appeal, but he must have the knowledge of what to say, and how to act, in order to gain admittance. Even then, he is not out of trouble. He finds himself caught in a double bind - behaving in a manner that suggests mental illness may imply dangerousness and affect their asylum claim, while demonstrating that they do not have a mental illness leads to a Breach of the Peace charge for the suicidal gesture, a relatively minor charge that is far more damaging to them than to the native who engages in the same public behavior. The health care worker responsible for assessing this refugee experiences a sense of moral injury, not unlike that experienced by clinicians working with Indochinese refugees in the 1980s in the Philippines Refugee Processing Center on the island of Bataan, who knew that documenting mental illness could open up access to care but jeopardize resettlement opportunities, while hiding it meant denying them access to available treatments and supports.4

A less dramatic case of medical borders involves the case of an international student in the UK who develops what could be a first-episode psychosis (FEP). The existence of an early intervention psychosis team that takes on all people under the age of 35 with suspected FEP and follows them up for two years is not enough to ensure that this patient will receive assessment and treatment. There will be the consideration that this is an international student unlikely to remain in the country beyond the course of their degree, making the service reluctant to waste this ‘precious resource’ on someone who may not be around long enough to experience a positive outcome. The patient in question has since moved back to their own country. I do not know if this vindicates, or is a consequence of, the service’s triage procedure.

Borders, Medical Screening, and Eugenics5

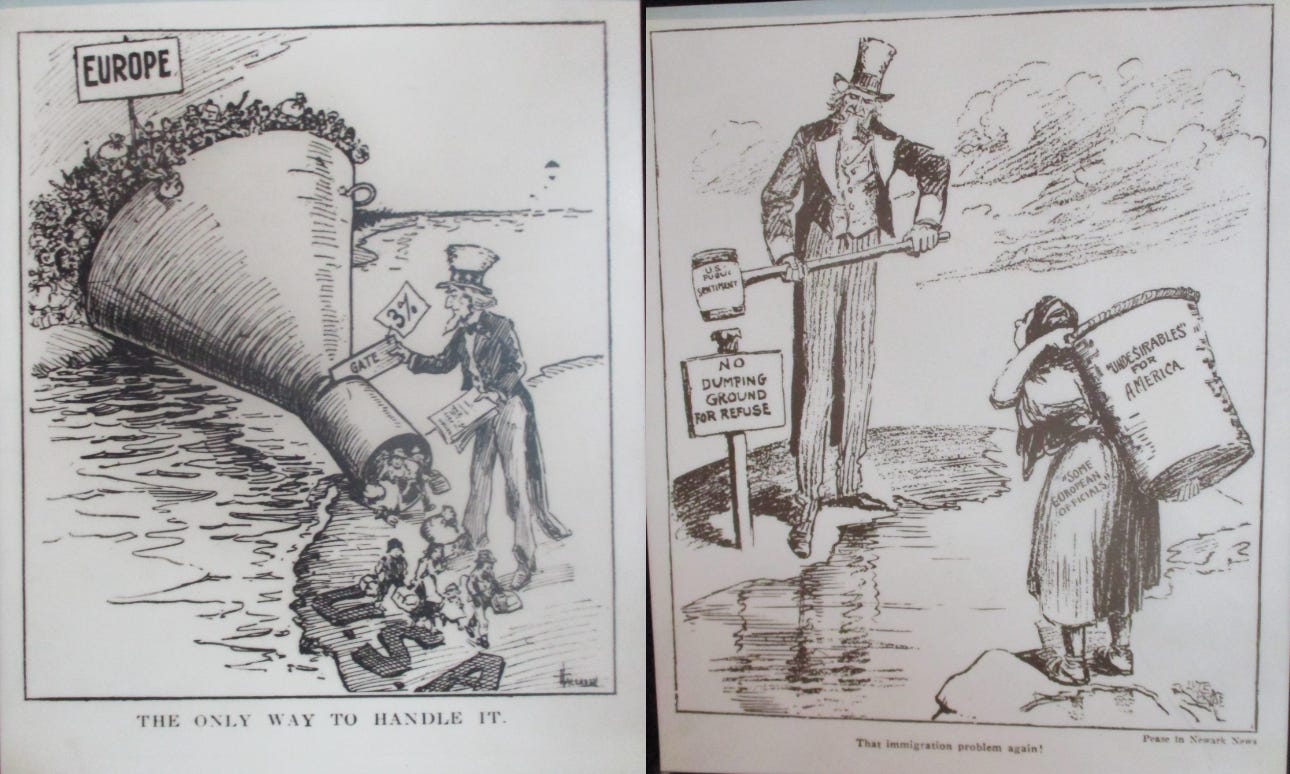

It may seem an overstatement to associate borders with eugenics, but it is actually quite logical. The term literally means ‘good breeding’, and was coined by Francis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin, in 1883 in Victorian England. It refers to the idea, respectable until the Nazis made it disreputable, that the genetic fitness of a population, and desirable characteristics associated with good genetic stock, could be engineered and expanded through selective breeding, as if humans were cattle. The most dire implications are that some humans are allowed and encouraged to reproduce, while others are sterilized and exterminated. In a less extreme form, the same logic applies to who is allowed to gain entry to a country and society. Anxieties about ‘degeneration’ of a country’s genetic and racial stock merge with anxieties about ‘contamination’ by ‘defective elements’, as the Irish were called by American psychiatrists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

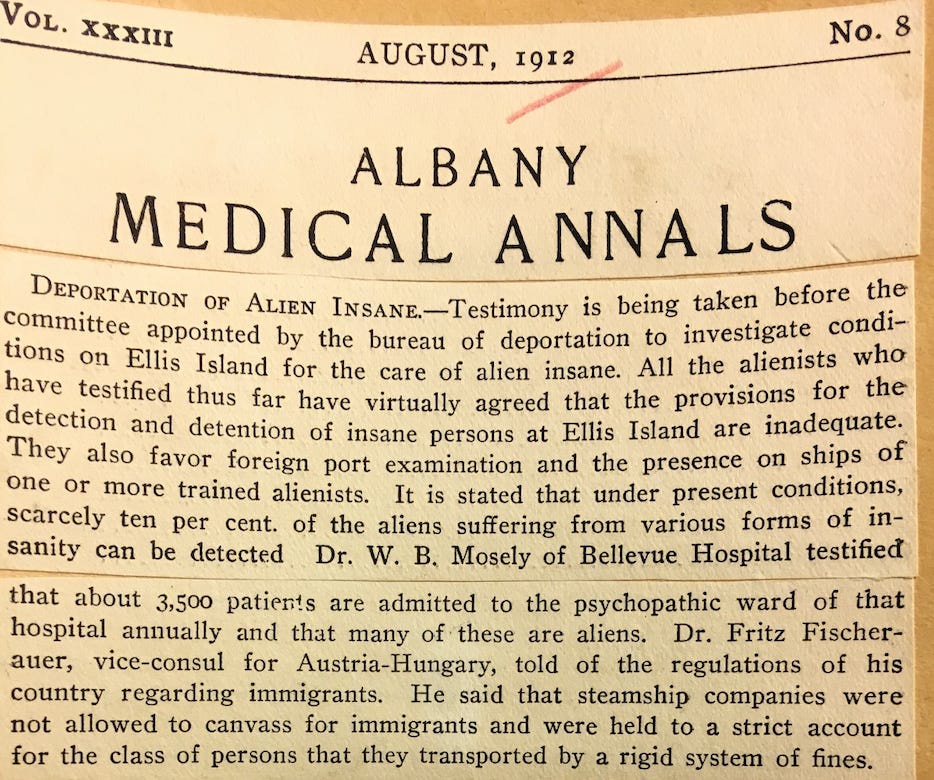

In 2020, while attending to unrelated archives at Cornell University’s Oskar Diethlem History of Psychiatry Library, I had a chance to look at the papers of Dr. Thomas Salmon, an American psychiatrist and pioneer in public mental health, or what was then called ‘mental hygiene’. Before the First World War, Salmon was chairman of the New York State Board of Alienists (an older term for psychiatrists). In the early twentieth century the population of the State of New York was increasing more due to immigration than to natural births. Anxieties about the importation of insane and unsuitable elements drove concerns about the state’s, and country’s, ‘mental hygiene’. Salmon’s work informed the thinking of the State Commission in Lunacy, which proposed to Congress in 1912 a set of amendments to the Federal Immigration Law, such as extending the time limit for deportation of insane aliens6 from 3 to 5 years, authorizing the government to fine ship companies $100 for every insane immigrant that landed in the US, and conducting mental examinations of all immigrants by a qualified medical examiner. Immigration to the US was curtailed on a national level with the 1917 law that mandated a literacy test for all immigrants, and a 1924 law that set a quota on how many immigrants could be accepted from certain countries. To this day, ‘a mental disorder which is associated with a display of harmful behavior’ can be grounds for refusal for a US visa.

We often think of a medical procedure as something that benefits the person who receives it. Why else would they subject themselves to it? Primum non nocere - first, do no harm, the Hippocratic oath is supposed to have said.7 What is the purpose of medical screening of prospective entrants to a country? It is not for the health of the person being screened, so it is not medically necessary. One cannot refuse to comply with medical screening requirements, so it is not voluntary. Their purpose is to exclude, so they are discriminatory. What is a word for a coercive, nonconsensual, medically unnecessary procedure that serves to discriminate and exclude? Eugenics.

Photo 1: 1912 snippet from the Albany Medical Annals on the deportation of the alien insane. This photo was taken from the Thomas Salmon collection at the Oskar Diethlem Library at Cornell University, New York City.

Photo 2: Early twentieth-century American anti-immigration propaganda. Photos taken at Ellis Island in 2019.

The story, Welcome to the Military, can be read here, though it feels odd to read something I wrote over a decade ago. Rowayat has since been reincarnated as a Canada-based non-profit.

The best book on this period of Egypt’s history is Khaled Fahmy’s All the Pasha’s Men: Mehmed Ali, his Army, and the Making of Modern Egypt.

I am indebted to the subreddit r/Antipsychiatry for this phrase.

This account is from Linda Hitchcox’s Vietnamese Refugees in Southeast Asian Camps.

This section has benefitted from conversations with my friend and fellow Global Mental Health MSc alumnus Sarah Oeffler, who is one half of The Leftist Cooks. She was recently featured, with her partner Neilly, the other half, in this Guardian article.

‘Aliens’ referred to both immigrants and psychiatric patients. The latter were alienated from themselves. ‘Alienists’ referred to those doctors (psychiatrists) who worked with aliens.

In truth, this phrase likely originated with Thomas Sydenham, familiar to medical students the world over because of his association with Sydenham’s chorea.